Office of Research & Development |

|

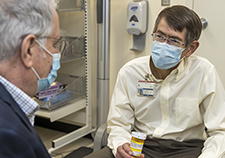

Internal medicine physician Dr. Howard Gordon sees patient Zachary Harris in the Fast Track clinic at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center in Chicago. (Photo by Chanda Johnson)

May 7, 2020

Erica Sprey

VA Research Communications

"Patients should not be afraid to speak up and ask questions, to challenge a physician's statement, or to jump in and share additional information."

A common view of physicians is that they use complicated language that is peppered with jargon.

While this may not always be the case, it can be a problem if patients feel they can't effectively talk to their doctors.

The danger in using language that patients don't understand is twofold: Physicians may not successfully communicate essential information to patients, and they may be less effective in building trust with their patients.

A team of VA researchers led by Dr. Howard Gordon at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center in Chicago studied diabetic patients' beliefs about their roles in communicating with physicians.

The study, published in BMC Health Services Research, found that Veterans' use of participatory (active) communication was influenced by their beliefs about their diabetes and their views of physicians' expectations.

Participatory communication emphasizes two-way dialogue. It encourages the sharing of opinions, information, and perceptions between speakers.

Veteran disability payments led to fewer hospitalizations

Study links statin use with diabetes progression, points to need for further research

Can statins help 75-and-overs stay healthy? PREVENTABLE trial will provide answers

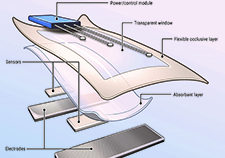

VA researcher develops 'smart bandage' technology for chronic wounds

Patients should feel comfortable asking their physicians questions, making requests, or expressing an opinion. If they don't, it could impact the effectiveness of their medical care, according to the researchers.

"Patients should not be afraid to speak up and ask questions, to challenge a physician’s statement, or to jump in and share additional information," said Gordon. It's not necessary for patients to know the "right questions" to ask, he added. The goal is to help patients feel comfortable discussing their concerns with the doctor.

However, studies have shown patients with chronic diseases or low health literacy, or who are minorities or part of other vulnerable populations, may find it more difficult to effectively communicate with their doctors.

"Understanding these barriers is important because patients who are less engaged and use less active communication may gain less understanding of their type 2 diabetes, may be less likely to adhere to treatment recommendations, and may have worse outcomes," wrote the researchers.

Because good communication skills go hand-in-hand with better outcomes, Gordon and his colleagues focused on Veterans who had high blood sugar.

The investigators held four focus groups, including 20 male Veterans in total, who had type 2 diabetes. Study participants were on average 61 years old; 65% were African American; 80% had completed high school; and all were from an inner-city VA hospital in Chicago.

Veterans in the study had an average hemoglobin A1C of 10.3%, which means that their blood glucose levels were significantly elevated. Typically, physicians strive to maintain an A1C of 7% or lower for patients with diabetes.

Hemoglobin A1C measures glucose that is bound to hemoglobin molecules in the blood. The test reflects the average level of glucose over a three-month period. An elevated A1C indicates excess sugar in the bloodstream, which raises a person's risk of diabetes complications.

The focus group members were shown a video similar to one developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality called "Questions are the Answer," to break the ice and introduce the topic of asking questions.

The Veterans were then asked a series of questions about their feelings on what it was like to have diabetes; how they felt about talking with their doctor; and how communication could be improved.

Recordings of the focus group discussions were transcribed and then assigned different "themes" by a coder to facilitate analysis.

After analyzing the data, the researchers grouped the themes into three categories: patients' beliefs about their condition; their views of physician communication behaviors; and external influences on patient-physician communication.

Patients' self-constructed beliefs: When it came to patients' beliefs about their diabetes, the researchers found that some Veterans in the focus groups were hard on themselves—accepting blame for not following provider recommendations.

Several Veterans also expressed embarrassment that their diabetes was not well-controlled: "Sometimes I'm ashamed about how I've been carrying on. I know I eat the wrong things. I know I don't exercise and my sugar's way too high."

Other Veterans took the opposite approach. They minimized the severity of their disease, by reframing acceptable blood sugar levels. For instance, one Veteran said, "[My sugar] is a little bit high. Never went over 400, so I consider that good."

Patients' perceptions of physician behaviors: Some of the Veterans indicated that they felt pressured by their physician, especially when the doctors used a paternalistic or lecturing style of communication. In these instances, Veterans distanced themselves by withdrawing.

They often described their feelings using adjectives that were reminiscent of their military service—"doing battle, shoots at me, bullet proof, and bootcamp." One Veteran shared: "The doctor shoots at me and I just bulletproof, I just take it. There's no negotiating with [Dr. …]"

Many Veterans said they had difficulty understanding their physicians when they used complex language. They also indicated that they felt intimidated, or at a disadvantage. One Veteran declared, "I'm battling an encyclopedia … they are talking from the Encyclopedia Britannica brain."

Patients' perceptions about external influences: In addition to patient and physician behaviors, the researchers also examined structural factors that could influence communication patterns. They found that lack of continuity in providers had a significant impact on Veteran satisfaction and trust.

"You get comfortable with a certain doctor and then they change you. They give you a new doctor, and then you have to start all over again," said one Veteran.

Another barrier was the use of a computer in the exam room. Veterans commented that they felt "ignored" when the physician was typing in the electronic health record (EHR). They also felt it was unnecessary to share information about themselves because "the doctor already knows my body, because the tests they have taken [are in the computer], so I just really answer the doctor's questions."

Finally, Veterans in the focus group were concerned about time constraints during the patient visit. They frequently indicated frustration with feeling rushed, and sometimes interpreted that as disinterest on the physicians' part.

"Well, if people are not going to take time with you, then that turns you off. You're not going to ask questions, if they don't want to have time."

There are a number of interventions that could help patients become better communicators, such as in-person coaches, noted the researchers. But often, they said, they are time-intensive and expensive to implement.

Gordon and his team proposed using an intervention similar to direct-to-consumer, TV drug ads, because it could be a less expensive alternative.

These types of TV ads are designed to influence patient behavior and prompt people to make specific requests during their medical visit—two factors that could benefit diabetes patients. These interventions could also have a positive effect on physician behavior, wrote the study authors.

"Pre-visit interventions that use positive role modeling by showing patients using active communication can help patients be prepared to speak up in their medical visits," said Gordon.

"These interventions could also alert physicians to expect patient questions and may be effective at improving doctor-patient communication and even patients’ health outcomes."

More research is needed to understand the full potential of these pre-consultation planning interventions, noted the researchers.

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates