Office of Research & Development |

|

Dr. Florian Schroeck is chief of urology at the White River Junction VA Medical Center in Vermont and an assistant professor at Dartmouth College. He has studied the cost-effectiveness of newer prostate cancer treatments such as robot-assisted surgery. (Photo by Mark L. Washburn/ Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center)

May 24, 2018

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

Newer treatments for prostate cancer (Infographic by VA Research Communications, May 2018)

Download PDF

Since the start of the 21st century, a series of new technologies have revolutionized the treatment of prostate cancer—in surgical and radiation procedures, and in detection and management of the disease. Basically, the standard of care has evolved over time.

However, the cost-effectiveness of these technologies, compared with more traditional treatments, has not been fully explored.

To learn more, researchers reviewed articles published from 2001 to 2016 in medical and scientific journals, with an eye on three of the innovations: robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP), intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), and proton beam therapy.

The research team found that treating prostate cancer with these procedures is more expensive than traditional options. But whether the increased cost translates into better care, thus making them worth the expense, is unclear.

Efforts to validate that are hampered by the uncertainty tied to improvements in outcomes, such as cancer control and side effects, the researchers say. They note if the new technologies can consistently achieve better outcomes, then they may be cost-effective.

The findings appeared in European Urology in November 2017.

"The interesting thing is that all of these changes happened without really good data showing that these new technologies are better."

Dr. Florian Schroeck, chief of urology at the White River Junction VA Medical Center in Vermont, led the study. He’s also an assistant professor at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire.

He calls for restraint on a rush to judgment on whether the innovations mean better care.

“Overall, I’d say there is some evidence that outcomes are slightly better with these new technologies, compared with their more traditional counterparts,” he says. “However, there’s still a lot of uncertainty about this, and findings may change with results of more rigorous studies.”

He adds: “The interesting thing is that all of these changes happened without really good data showing that these new technologies are better. But the surgeons liked it, and the patients liked it, and the companies have been very smart in selling the technologies. In most parts of the world, robotic surgery and IMRT have completely taken over treatment. That’s what people get now.”

Gauging the cost-effectiveness of these new technologies in a scientifically valid way, Schroeck says, is “very challenging.” He notes that the process becomes complicated when trying to measure outcomes.

“The two important measurements are quality-of-life outcomes in terms of urinary and sexual function after treatment,” he says. “Validated questionnaires measure that, but it’s work to complete them. The shortest one is two or three pages long. Someone must hand them to the patient and collect them after the patient fills them out. So having good data on how patients do post-operatively that is measured in a valid way is challenging.”

Schroeck says the most commonly used questionnaire is called EPIC, which is designed to measure quality-of-life issues in patients with prostate cancer.

VA researchers using AI to decide best treatment for rectal cancer

VA center training the next generation of researchers in blood clots and inflammation

AI to Maximize Treatment for Veterans with Head and Neck Cancer

Veterans help find new cancer treatments

He further explains that in an observational study, biases can potentially impact how one feels even if the quality of the surgery is the same. For example, a person who is wealthy and young with no co-occurring diseases may feel differently post-surgery than someone from a different socio-economic background, he says.

Thus, Schroeck is eager to learn the results of an ongoing Australian-based randomized trial that is comparing the effectiveness of robotic laparoscopic surgery to that of its predecessor, open radical prostatectomy. Both procedures involve removal of the prostate. But laparoscopy, which means to look inside the abdomen with a special camera or scope, is less invasive than open surgery.

Robotic surgery is not nearly as common in Australia as it is in the U.S. “With longer follow-up, that trial may shed some more light on this because you don’t have to deal with all of these biases,” he says.

More than 80 percent of prostatectomies in the United States are done robotically.

Prostate cancer, the second-leading cause of cancer deaths among men, is most common in men age 65 and older. The disease is usually found in its early stages, typically as the result of a PSA (prostate specific antigen) blood test, and often grows slowly. It may take many years for a tumor to become large enough to be detectable and even longer to spread beyond the prostate. Most men live with the cancer for decades without symptoms and die of other causes even without early surgery.

Dr. Timothy Wilt, a physician-researcher at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System, led the PIVOT study. The landmark VA trial of nearly 20 years concluded that surgery doesn’t significantly reduce all-cause or prostate cancer deaths for men who are diagnosed in the early stages of the disease. Wilt is also well-known for his reviews and meta-analyses on treatments and their cost-effectiveness.

He and his colleague on the PIVOT study, Dr. Philipp Dahm, are skeptical that the new technologies reviewed in Schroeck’s study are worth the expense. They said in a jointly authored email that “none of these therapies have proven superior to their standard [predecessor]. None should make other therapies obsolete from a scientific and clinical outcomes standpoint.”

They add that all three technologies “are part of standard practice, and therein may lie some of the problem. They provide little to no difference in clinical outcomes, such as urinary and sexual function.”

The technologies examined in Schroeck’s study relate to surgery or radiation therapy, the two most popular forms of treatment for men diagnosed with early-stage localized prostate cancer.

Radical prostatectomy is when a surgeon removes the walnut-sized prostate. In robot-assisted radical prostatectomy, a surgeon sits at a control panel and moves robotic arms to operate through incisions in the patient’s abdomen, with the goal of removing the prostate. The robot’s arms replicate the surgeon’s hand movements. The procedure is minimally invasive: The incisions are smaller than in traditional open surgery. And it is laparoscopic, meaning the surgeon uses a pencil-thin video camera to view inside the body.

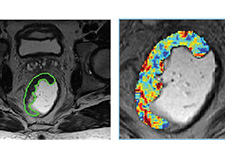

Intensity-modulated radiotherapy has essentially replaced three-dimensional (3D) conformal radiotherapy, a form of prostate cancer treatment that shapes the radiation beams to match the shape of the tumor. IMRT features beams that can provide multiple intensity levels for any single-beam direction and any single-source position. It’s ideal for avoiding organs, such as the rectum or bladder, that lie in close proximity to the cancer.

In proton beam therapy, energy is carried by protons, the positively charged particles in an atom. The proton beams stop after releasing their energy within the intended target, unlike protons in X-rays. Higher doses of radiation can be more safely delivered to tumors with less risk to healthy tissue.

Schroeck’s team says treatment with any of these technologies comes with major upfront costs. Case in point: Hospitals can spend more than $2 million for a robotic platform and more than $150 million for a proton beam therapy facility.

But some of the costs may be offset by better outcomes or less resource use during the procedure, the researchers say. For example, fewer adverse events and shorter hospital stays linked to robotic surgery may counter some of the extra expenses.

The study team compared the costs of the three technologies with those of their more traditional counterparts:

In rating the cost-effectiveness of new versus older technology at this time, Schroeck says: “The cost-difference between RARP and open surgery is the smallest. The cost difference between proton beam therapy and IMRT is the largest; thus, proton therapy has the least potential of being cost-effective.”

RARP and IMRT have become the “de facto standard of care” at most VA and non-VA facilities, he notes.

“This has been driven largely by provider and patient demand, much more so than by solid scientific data,” he says. “However, as volumes increase and outcomes continue to improve, these new technologies will likely ultimately prove to be worth it. Regarding proton therapy, it is very complex and costly to start a proton therapy treatment center. As such, it is less likely that this technology will disseminate as widely as the other two.”

Schroeck’s team says understanding the value of treatment with new technologies will become more important as society and policymakers move to accountable care organizations, which are groups of doctors, hospitals, and health care providers who give high-quality care to Medicare patients; to value-based reimbursement, which ties payments for care delivery to the quality of care provided and rewards providers for efficiency and effectiveness; and to bundled payments, a strategy to reduce health care costs through a payment made to providers for services based on the expected costs of a treatment.

In addition to the private sector, these trends may have important implications for VA, particularly as the agency moves toward buying more complex equipment for robotic surgery and IMRT, according to Schroeck.

“Since value is defined as outcomes relative to cost, we will need more accurate ways of capturing cost and outcomes of treatment using approaches, such as prospective population-based prostate cancer registries,” Schroeck and his colleagues write. “We encourage physicians and patients to participate in such registries whenever possible.”

Will a study be conducted that provides a more accurate picture of whether these new technologies are worth the cost?

“Everything really hinges on producing more certain results in terms of whether the outcomes are really better with the new technologies,” Schroeck says. “I would hope that the Australian trial will shed some more light onto this. “Once this has happened, updated cost-effectiveness analyses will likely be performed.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates