Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

September 17, 2014

Veteran Charles Condrotte, now retired, holds a picture of himself from when he was a forest ranger. Still an active hiker, he took part in a Phoenix VA study in which he received a kinematically aligned knee replacement. (Photo by David Hodge)

Each year, more than half a million patients in the U.S. receive a total knee replacement, and roughly 20 percent of them are dissatisfied with the results, says Dr. Gene Dossett, chief of orthopedic surgery at the Phoenix VA Health Care System.

The main reason? Persistent pain, even after the replacement.

So Dossett and a small team of VA doctors completed a two-year clinical study comparing traditional replacement methods with a newer method in hopes of improving patients' pain levels, function, and range of movement.

The new method, called kinematic alignment, uses MRI scans and special software to create customized cutting guides that the surgeon uses to prepare the bones surrounding the artificial knee. The result is a more personalized fit.

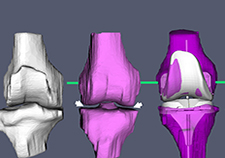

In kinematic alignment, 3D models of patients' knees, based on MRI scans, are used to create personalized cutting guides that surgeons use to prepare the bones around the artificial knee. (Image courtesy of Dr. Gene Dossett)

The new method is not yet commercially available, and little formal research on it exists. The new VA study was the first randomized, controlled trial comparing clinical results between kinematic and conventional alignment. Dossett's team published the results in July 2014 in Britain's Bone & Joint Journal.

"What we found is that kinematic knee replacement provided much better pain relief and was more effective in restoring function and range of movement," says the surgeon.

Among the 88 Veterans who took part in the study, those who received the kinematically aligned knees were more than three times as likely to be pain-free at two years, compared with those whose procedures had used conventional mechanical alignment. They also were able to walk 50 feet further, on average, in the hospital prior to discharge.

In the study, neither the patients nor the clinicians who evaluated them knew which of the two styles of alignment had been used.

The same knee-replacement procedures have been used by orthopedic surgeons for nearly 30 years, says Dossett: Align the bones in the leg, from the hip to the ankle, and cut the bones at 90-degree angles to allow for the prosthesis.

Kinematic alignment uses a more individualized approach. The bottom of the thigh bone and top of the shin bone are cut using personalized guides, made of hard plastic. The guides are fabricated based on patients' MRI scans and 3D models of the knees generated by special software.

The guides fit the end of the bones to create the cutting angle and resection depth for each patient's knee. The goal is to reproduce a more natural position for the patient's knee—similar to how it was prior to arthritis setting in.

Both types of surgeries use the same cobalt chrome prosthesis.

Veteran Charles Schmidt, the first patient to undergo the kinematic technique as part of the Phoenix VA study, reported that before his surgery, he was in pain every time he tried to walk.

"My new knee is my strongest knee," Schmidt said. "Now I'm totally pain-free and have been since the operation and rehab. The best thing to say about it, I guess, is that I don't think about it anymore."

Schmidt said that since the surgery, he's taken extended trips to South America without any problems from his knee. He said he soon will leave for a tour of Spanish cities.

Another recipient of the kinematic knee, Charles Condrotte, has also traveled extensively since his operation in 2009. He said he's been to China, Great Britain, and several countries in Europe, and has taken part in safaris in Tanzania and Kenya. He plans to visit Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Galapagos Islands in the near future.

After retiring from the Navy, he worked as a forest ranger in Flagstaff, Ariz. He said he's logged more than 2,000 miles of hiking mountainous trails.

Before surgery, his knee reached the point where the pain was constant and always on his mind—limiting his work and personal life. Afterwards, Condrotte said, he's been pain-free.

"I still hike a lot up in Flagstaff," Condrotte said, now retired from the Forest Service after 17 years. "We have some wonderful trails."

"I've had fantastic care at the VA," he added. "They do a wonderful job."

Meanwhile, Dossett says he is "using the knowledge gained from this study to continue to help Veterans obtain the best possible results from their knee replacement."