Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

February 12, 2015

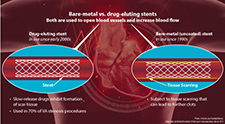

Bare-metal vs. drug-eluting stents (Infographic by Michael Escalante, VA Research Communications, March 2015; Photo: ©iStock.com/SomkiatFakmee)

A study on the safety of drug-eluting stents (DESs) showed they were just as safe as bare-metal stents for use in vein grafts. In the study, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology on Oct. 28, 2014, patients who received a DES had lower long-term mortality rates than those who received a bare-metal stent. The odds of having a myocardial infarction, also known as a heart attack, were the same between the two groups.

"They [DESs] didn't perform worse. That's the way we've been thinking about it," says Dr. Thomas Maddox, a staff cardiologist at the VA Eastern Colorado Healthcare System in Denver. "The main question we had was, are they safe, and the answer from this data was yes."

Drug-eluting stents, which came into wide use over the past decade or so, are similar to traditional, or bare-metal, stents, in that they're placed into narrowed blood vessels to act like a scaffold and prevent the vessel from collapsing. But, while bare-metal stents can sometimes be absorbed by scar tissue or become clotted themselves, DESs are coated with immunosuppressive drugs. Over time, the drugs are released, preventing scar buildup.

"When bare-metal stents were developed in the 1990s, they were a huge improvement over what we were doing, but even then, around 5 to 20 percent of the time [the stent] gets plugged up and you can't take it out because it's embedded in the tissue," says Maddox, who is also an associate professor at the University of Colorado. "Generally you can open it up again and push the scar tissue to the side or put in another stent, but as you can imagine, there's only so many times you can do that. Once we had drug-eluting stents in place we saw those numbers plummet to well below 5 percent."

As one might expect, the use of DESs are up across the board, both in VA and nationwide. Roughly 70 percent of the stents used in VA procedures today are drug-eluting.

The concern, says Maddox, is that not all vessels are the same. In a coronary artery stenosis, for example, stents are placed directly into the coronary artery. In those cases, the efficacy of DESs is well-documented. Less well-known, however, is how they perform in other situations.

Say, for example, a saphenous vein graft, which involves lifting a vein from the leg and actually rerouting around the blockage in much the same way one might navigate a detour on the highway. "The difference there is the kind of vessel," says Maddox. Not only that, but "these are blood vessels in a different place than they were when you were born. They're more fragile, and we wanted to understand their response. We wanted to make sure we weren't inadvertently exposing patients to harm."

Maddox, along with other investigators from both VA and academia, studied data from 2,471 Veterans who received saphenous vein grafts from 2008 through 2012. Overall, 63 percent of the patients in the cohort received a DES, but the use of DESs actually grew from 50 percent in 2008 to almost 70 percent by 2011.

Complications with the procedure were under 3 percent in both groups, suggesting that DESs are every bit as safe for these types of grafts as BMSs. What's more, when compared over time with the BMS group, those who received a DES tended to have a lower risk of death.

Maddox explains, though, that the apparent edge of DESs in terms of increasing survival may be at least partially due to the fact that doctors tend to use DESs more commonly in healthier patients, and avoid them in sicker patients, although that is something the study attempted to control for.

"We don't really think the stents prevented them from dying. Rather, we tend to put drug-eluting stents into healthier people and, perhaps more importantly, with DESs, patients receive additional antiplatelets for a year, on average, after the procedure."

The presence of an antiplatelet, which inhibits the formation of blood clots, could be responsible for the lower mortality rate, though, as Maddox puts it, "there are no free rides." The use of antiplatelets can increase the risk of bleeding episodes. He says future studies should build this factor into their analysis.

"We're going to need more studies like this," he says. "We do roughly 1,000 of these procedures in VA every year, and every year companies are innovating on their stent types. As they come to market, we need to be aware so that we can make sure that the 70 percent of Veterans [undergoing stenting] who receive drug-eluting stents are safe. That was the big question here: Are we doing everything we can to ensure these Veterans are getting safe care? That's why we did this study, and we were happy to see it's true."