Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

February 26, 2014

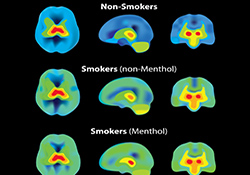

As shown in this lab graphic, smokers' brains—especially those who use menthol cigarettes—have more nicotine receptors, which makes cravings stronger. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Arthur Brody/VA-UCLA)

Veterans smoke cigarettes at higher rates than their civilian counterparts, a sobering thought given that some 21 percent of the general population regularly smokes. And, while studies have shown that the vast majority of smokers would like to quit, nationwide only about 4 percent of smokers who try to quit actually succeed.

Dr. Arthur Brody, a neurologist with the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and UCLA, knows how hard it is for smokers to quit. For more than 16 years he's worked on the front lines of the fight against smoking, spearheading technological achievements—most recently, using functional brain imagery—to find out just how tobacco addiction occurs and testing virtual reality treatment to help make quitting easier.

"I've seen people quit cold turkey," says Brody. "They don't want to smoke anymore or their doctor tells them their lungs look bad and they go to the drug store, pick up a nicotine patch and give it a go. It certainly happens, but we're talking about a very low success rate. Those kinds of efforts usually don't work."

Brody, who says tobacco addiction can be as tough as quitting drugs like heroin, amphetamines, or cocaine, believes smokers have a much better chance of kicking the habit if they take a comprehensive approach.

Researchers are exploring a variety of new technologies to help smokers break the habit. (Photo by Senior Airman Anthony Sanchelli/USAF)

To help them, he and VA researchers across the country are pioneering new technology that helps visualize what happens in the brain when people smoke, and what their cravings look like biologically. The goal is to find more effective treatment. Brody, who published a comprehensive review of anti-smoking science in the January 2012 Journal of Addiction Research and Therapy, believes an improved understanding of the brain will lead to higher quit rates.

Smoking, as it turns out, makes you feel good. Or more accurately, it causes dopamine to be released—not as much as some other drugs, but enough to reward the body. That, says Brody, results in pleasurable feelings and eventual dependence. What's worse, smoking actually causes the brain to develop more nicotine receptors, parts of the brain hungry for nicotine. When those receptors don't get their fix, smokers undergo withdrawal.

Brody and his team studied functional brain imagery of both smokers and non-smokers to better understand the effect nicotine and the more than 4,000 other chemicals in cigarettes have on the brain. "We still don't know the full story," says Brody, who cites menthol cigarettes as an example. Menthol smokers have far lower quit rates than those who smoke traditional cigarettes. Brain imagery shows that menthol affects the brain differently, but discovering how to aid menthol smokers in quitting is still a step away. That study was published in the International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology in June 2013.

Still, Brody remains optimistic. "The brain imaging is teaching us more about how the brain works when people smoke, when they crave, and when they quit. And the more we know about the chemicals at play and the transmitters involved and the regions of the brain affected, the more likely we can develop a treatment," he says.

The plan is this: Scientists find a specific nicotine receptor in the brain that appears to play a key role in certain cravings. The drug industry then develops a medicine that delivers a targeted strike against a smoker's strongest cravings. This, says Brody, is the key to success.

"All of our treatments are about helping with cravings," says Brody. "The medications we use, nicotine replacements, and even psychotherapy are all aimed at fighting the cravings. People come back to me and admit that they still want to smoke, but that the medicine has taken the edge off. It's made it manageable."

To that end, Brody and researchers at UCLA even used a virtual-reality tool to overcome common experiences that might cue smoking cravings. Using the popular online virtual world Second Life, VA researchers exposed participants to a variety of scenarios specifically designed to stimulate their desire for a cigarette. For some, that might be a cup of coffee or the sight of their favorite cigarette brand. For others it might be as simple as waiting at the bus stop.

The researchers also combined the virtual reality with traditional treatment and psychotherapy and found, at the end of six months, that smokers exposed to virtual reality not only reported smoking less, but also had a higher success rate with quitting.

"The sample size was small," says Brody, "and I wouldn't describe it as a common treatment, but it shows promise for the future."

Brody describes transcranial magnetic stimulation, a treatment program involving the application of magnets to stimulate parts of the prefrontal cortex, in similar terms. It's another promising technology, he says.

While not every new technology will prove to be the next nicotine patch, it's the growing body of knowledge on how cigarettes affect people biologically that eventually may make the difference.

And according to Brody, the answer may ultimately lie not in one treatment, but in a combination of treatments.

"I don't think they're going to make cigarettes illegal anytime soon and it is incredibly hard to quit smoking," says Brody, "so the best option left is comprehensive treatment" to help people kick the habit.

One problem VA researchers have encountered is verifying self-reported tobacco abstinence among Veterans. In other words, if a smoker claims to have quit but really has not, that can obviously throw off the results of a study. A recent study by Drs. Devon Noonan and Sonia Duffy of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the University of Michigan found that as many as 21 percent of Veterans who claimed to have abstained from smoking were not reporting the truth.

The study, which ran in the March 2013 issue of the journal Addictive Behaviors, called for biochemical proof in future studies to ensure accuracy. "The misclassification rate among self-reported quitters was about one in five," says Duffy. "In order to identify true quit rates, we need to use biochemical testing."

The researchers suggest something as simple as a urinary test strip to address the problem.

Unfortunately, the tests are expensive. Individual biochemical validation can cost as much as $7 per test strip, plus up to $40 for laboratory work. This is not including the burden on Veterans to provide the samples.

Still, the researchers feel the extra work is worth it. "VA has spent a tremendous amount of money on assisting Veterans to quit smoking and also funds a considerable amount of research on smoking cessation," wrote the authors. Duffy asserts that to identify effective approaches, researchers first need to ensure they have accurate data on whether smokers are really quitting.