Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

October 8, 2014

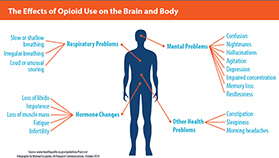

Source: www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Pain/cot/ (Infographic by Michael Escalante, VA Research Communications, October 2014)

Most people think of pain as an objective physical sensation generated by the body, but it is really a subjective experience generated in the brain. That's why two people may have very different pain reactions to the same type of injury. And when pain is chronic—lasting longer than three months—those reactions, both physical and mental, can have huge effects on quality of life.

A 2011 Institute of Medicine report pegged the nationwide cost of chronic pain at up to $635 billion each year in medical bills, missed work, and lost productivity.

The most common type of chronic pain—defined as pain lasting longer than three months—is musculoskeletal. Think arthritis, knee, hip, and lower back pain, and, literally, pains in the neck.

"Chronic pain is such a devastating issue. It profoundly affects Veterans, not just physically, but emotionally. It's strongly associated with depression. It interferes with work, recreational activities and a patient's social life," says Dr. Mathew Bair, a core investigator at VA's Center for Health Information and Communications in Indianapolis. "It's important that we treat chronic pain, and the most common way we treat it is with medication."

To treat pain, providers have turned increasingly to opioid analgesics, psychoactive drugs that derive naturally from the poppy plant, such as morphine and codeine, or that are made synthetically, such as methadone and oxycodone. Morphine has been a staple in battlefield medicine since the Civil War, while synthetic opioids became widespread later on.

(The terms "opiate" and "opioid" are often used interchangeably, but technically, opiates derive naturally from the poppy plant, which contains opium, whereas opioids are wholly or partly synthetic. Both classes of drugs produce similar effects in the body.)

"Opioids can be beneficial in many ways. Veterans suffering from acute pain, wounds, or even end-of-life issues can greatly benefit from their use," says Bair, also an associate professor of medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine.

"In any given year about a third of Veterans in VA care are prescribed an opioid," adds Dr. William Becker, an investigator at VA's Pain Research, Informatics, Medical Comorbidities, and Education Center, and a professor at Yale. "Of those, a third are on long-term opioid prescriptions." The numbers, say Becker, are indicative of the civilian population as well. "Nationally, opioids are the most commonly prescribed medication."

The downside, though, as Bair points out, is that "for patients with chronic pain, opioid use can carry with it a host of undesired side effects."

He says the nationwide rise in emergency room visits and opioid-related deaths has led to increased scrutiny over pain management practices, not just in VA, but in medical care in general.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, prescriptions for opioids nationwide increased by 400 percent from 1999 to 2010. Opioid overdoses, meanwhile, also increased by 400 percent across the country.

Bair and his team in Indiana are gearing up to test one way to deal with the problem. His study titled "Care Management for the Effective Use of Opioids," or CAMEO, will recruit 300 Veterans with chronic back pain who are currently prescribed opioids. The researchers will split them into two groups. One group will continue to receive their opioid therapy. The other group will be taken off opioids and will meet regularly with a psychologist and undergo cognitive behavioral therapy.

That therapy will include eight 45-minute pain management and coping sessions. Researchers will follow up with the participants at two, three, four, six, and nine months. When the study is over, Bair hopes to be able to point to definitive results on the effectiveness of psychological approaches to pain management.

"This is one of the first studies comparing a pharmacological approach to a psychological approach," says Bair. "Our Veterans are suffering and we need better treatments."

Veterans in Indiana who are currently on opioid therapy for chronic pain can volunteer for the study by going to www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Many of those who take opioids for pain also have mental health diagnoses. Unfortunately, such patients are at a greater risk of misusing the drugs.

A 2012 study of more than 141,000 Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans with non-cancer pain found that those with mental health diagnoses—especially PTSD—were more likely to be on prescription opioids. They were also more likely to be receiving risky combinations of opioids, or opioids and other drugs. Not surprisingly, they were also more vulnerable to overdose or other bad outcomes related to opioids.

"The use of opiate pain medications in those patients is, frankly, risky," said the study's lead author Dr. Karen Seal, with VA and the University of California, San Francisco, in an interview with the American-Statesman.

Dr. Jodie Trafton, director of the Program Evaluation and Resource Center in Palo Alto, Calif., part of VA's Office of Mental Health Operations, says a new informed consent process that VA has launched should benefit all Veterans with pain, including those with PTSD or other mental health challenges.

"VA has just initiated an informed-consent mandate for chronic opioid therapy and the idea is that before a patient can even start, their doctor has to go through a very specific walkthrough of risks and benefits so that it's clearly a shared decision," says Trafton. "Patients often aren't aware of the risks of opioids and the general lack of evidence for long-term benefits. When presented with balanced information and their full range of options, many patients may choose other methods of pain management."

In addition to informed consent, VA has piloted education programs and reported dramatic drops in opioid prescriptions and subsequent adverse reactions. The Minneapolis VA Medical Center, for example, started a program called the Opioid Safety Initiative, which provided greater emphasis on non-drug pain-management strategies such as yoga and exercise. It resulted in a dramatic 94 percent drop in oxycodone prescriptions.

On a national scale, VA's Office of Research and Development has teamed with VA Pharmacy Benefits Management to develop an "opioid dashboard" for tracking prescriptions and dosages as part of the effort to help reduce the number of Veterans receiving high-dose or multiple prescriptions.

"It's about rethinking chronic pain from the moment a patient approaches their doctor," says Becker. He is a big proponent of VA's multimodal model, which addresses pain care using a variety of techniques, from acupuncture and yoga to behavioral cognitive therapy and physical therapy. "VA is extremely robust at providing these evidence-based treatments for chronic pain. Some people call them alternative treatments, but I like to think of them as central to every treatment plan. They're just as effective and often more effective at treating chronic pain, and they have very few, if any, side effects."

Seal, considered one of the preeminent experts on the emerging field of opioid use and PTSD, came to similar conclusions through her research, calling for more emphasis on non-pharmacologic therapies and integrated treatments.

The important thing is to focus not on the pain, but on life recovery, says Becker. "Patients should try to take the long view," he says, "and ask themselves what steps they need to take to regain the abilities they've lost. The answer should involve a combination of treatment because, unfortunately, even when opioids seem to be working, in the long term, they ultimately will have negative consequences.

"The good news is, this is a high priority in VA and Veterans should feel empowered by the effort VA is making here."