Office of Research & Development |

|

Office of Research & Development |

|

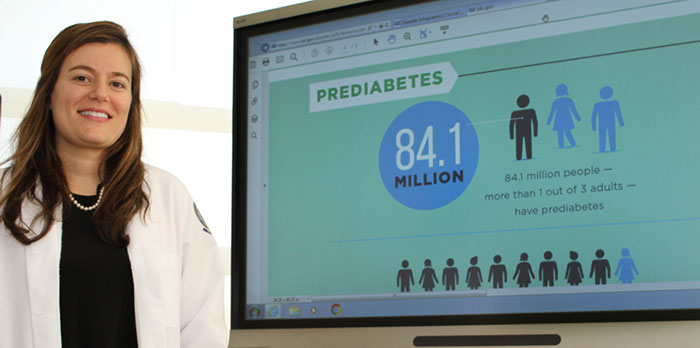

Dr. Tannaz Moin, an endocrinologist at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, led a study comparing different approaches to weight loss and diabetes prevention. (Photo by Scott Hathaway)

February 5, 2019

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

More than 80 million adults in the United States have prediabetes, meaning their blood sugar levels are elevated to the point where they may be at risk for full-blown Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes, a chronic condition in which the body is not properly making or using the hormone insulin, is a leading cause of blindness, kidney disease, amputation, and death.

A major risk factor for diabetes is obesity. Nearly 80 percent of Veterans are overweight or obese.

With research showing it’s possible for people with prediabetes to prevent or delay diabetes by improving diet, losing weight, and exercising more, VA researchers tested the effectiveness of an online version of the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) that features those three elements (see sidebar). They compared the online DPP to an in-person DPP and to MOVE!, VA’s flagship weight management program. Those participating in the study were overweight or obese Vets with prediabetes.

"Participants felt like they were part of a community in which they can connect with other people in the group and with their coach."

The Veterans in the online DPP lost an average of 10.6 pounds at six months and 8.08 pounds at one year, compared with 2.4 pounds at six months and 0.2 pounds at one year for the MOVE! participants. There was no statistically significant difference in weight loss between the Vets in the online and in-person DPP groups, prompting the researchers to conclude: “An intensive, multifaceted [online] DPP intervention may be as effective as in-person DPP and help expand reach to those at risk.”

Dr. Tannaz Moin, an endocrinologist at the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, was the lead author of the study. It appeared in the American Journal of Preventative Medicine in November 2018. This is the first time, she says, researchers have compared the online DPP to the in-person DPP and to MOVE!, which is also an in-person program. The online and in-person DPPs included essentially the same key program elements: emphasis on a low-fat diet focusing on seven percent weight loss, at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week, such as fast walking, and a calorie-reduction goal that depended on the starting weight of the participant.

Moin and her team weren’t surprised that the online and in-person DPPs, which follow recommendations made by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), led to similar degrees of weight loss. Both programs included identical features that helped to engage the participants: a human coach who gave one-on-one feedback; the regular delivery of educational materials on healthy eating and exercise to build skills and confidence toward achieving weight-loss goals; and closed group sessions in which the same participants maintained physical activity and diet logs and kept each other accountable.

MVP study offers new insights on genetic risk for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Veteran disability payments led to fewer hospitalizations

Lab studies seek hormone-based obesity treatment

Closed groups and self-monitoring, including dietary and physical-activity logging, are key components of the CDC standards in the DPPs.

In terms of the greater amount of weight loss in the DPPs compared to MOVE!, Moin points out that the three VA medical centers with MOVE! that took part in the study weren’t representative of the approximately 150 VA facilities that offer the program. Each of the three sites provided “less intensive treatment than DPP,” she says. In MOVE!, there were no specific group lifestyle goals, participants could attend different groups, and facilitators varied between sessions.

Moin notes that the study results were “absolutely valid,” although the research included only three of the 150 MOVE! sites. Doing a study with all 150 would have been “too costly and too time-intensive,” she says. The plan was to choose three sites that were geographically diverse, with the hope that they’d represent the broad array of MOVE! sites in a general sense. In addition, the researchers did not change anything about the way MOVE! is delivered to participants, although the number of sessions varies from site to site.

Unlike the in-person DPP and MOVE! programs, the online DPP offered features that increased flexibility and convenience for the Veterans. Online participants could remotely connect to the program at any time., and a human coach monitored online group interactions and gave feedback to the Veterans. The participants interacted with coaches mostly by phone or private online messaging or both and could post online messages to group members.

Plus, only the online participants received a wireless digital scale, allowing the coaches to remotely track everyone’s weight. Veterans in the in-person DPP and MOVE! programs traveled to a VA site to get weighed, one reason participation was greater in the online program, Moin says.

“The online participants knew someone was looking at this information,” says Moin, who is also an assistant professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Some of those Veterans told us in interviews that they felt someone cared and was following their progress. So there was accountability in the online program like there was in the in-person DPP.”

Veterans in the online DPP could also complete sessions anywhere and anytime, another element of convenience that the in-person DPP and MOVE! participants didn’t have.

Essentially, the online program involved more than just logging in and reading information.

“Imagine kind of a virtual group environment that can be accessed at any time,” Moin says. “You’re logged into a secure group that you and only a few other people can see. There are shared group goals, so you are in some ways also working as a team. Participants felt like they were part of a community in which they can connect with other people in the group and with their coach. The coach not only monitored the online environment but actually called the participants to check in, as well.”

The participants in the in-person program also benefited from a feeling of team unity, she adds.

In follow-up interviews, the online participants praised the program mostly for its ease and convenience, and the measure of accountability that it provided. For example:

Moin explains that since completion of the study, officials at VA’s National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, which oversees MOVE!, have disseminated new guidance to align MOVE! more closely to DPP. The guidance, based on results from the study, includes increasing the number of sessions at MOVE! sites and incorporating closed groups led by the same instructor. One recommendation is for a new minimum of 12 MOVE! sessions and 16 in total to better resemble DPP.

The redesign of MOVE! has occurred on the national level, but implementation of the updated recommendations may vary by site, Mon says. DPP enrolls only people with prediabetes, but MOVE! doesn’t restrict access based on a person’s blood sugar status, meaning people with diabetes, prediabetes, and even normal blood glucose levels can participate.

Moin notes that no bonafide online weight-loss program is now available in VA, although MOVE! also offers telephone and app versions.

“However, because weight-loss outcomes were similar between the online and in-person DPP programs tested in this trial,” she says, “we should consider ways to make a similarly intensive feature-rich online weight loss program available in VA. This could help expand access to more Veterans who may benefit from weight loss but are unable to participate in other available VA programs.”

The DPP initiative was developed from a large trial sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the results of which appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2002. The study showed that an intensive lifestyle change program, now referred to as DPP, was linked to a 58 percent reduction in the risk of Type 2 diabetes, compared with a placebo.

Moin has led a series of papers that analyzed DPP. Her 2015 pilot study, which included 17 female Veterans, concluded that the online DPP appeared to be a promising means of applying the program to female Veterans with prediabetes. The researchers found that the Vets in the study lost more than five percent of their weight on average over a 16-week period.

In a 2017 study that included 387 overweight or obese Veterans with prediabetes, Moin and her team compared the in-person DPP with MOVE!. The researchers found that DPP resulted in a greater loss of weight than MOVE! at the six-month mark: 9.0 pounds versus 4.2. At 12 months, the DPP Veterans weighed 7.5 pounds less than when the program began and the MOVE! Veterans 4.4 pounds less. Moin attributed the difference at six months mainly to the greater number of group sessions the DPP participants could attend.

Moin’s most recent study included more than 650 overweight or obese Veterans with prediabetes: 268 were enrolled in the online DPP, 273 in the in-person DPP, and 114 in the control group, MOVE! DPP participants were from the VA medical centers in Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Baltimore, and Milwaukee, the latter of which enrolled only female Vets. The MOVE! Veterans were from the VA facilities in Los Angeles, Baltimore, and Minneapolis.

The researchers assigned the online participants to groups using a formula based on age, body mass index (BMI), and geographic location. BMI is a measure of a person’s weight relative to his or her height and determines if someone is overweight or obese.

The online and in-person DPPs both included 22 sessions, 16 in the first six months and six in the last six months. Participants were assigned to one group with the same coach for the year-long period. MOVE! consisted of 8 to 12 core healthy lifestyle sessions during the same period.

The online DPP had greater participation than the in-person DPP and MOVE! Eighty-seven percent of online participants completed eight or more sessions, compared with 59 percent for the in-person program and 55 percent for MOVE! That difference, according to Moin, stems partly from the fact that the online modules were designed so participants could complete them at a convenient time, whether it was 8 a.m. or 11 p.m. New modules became available every week during the year-long period.

“We now know that the number of sessions attended by participants is highly correlated with weight-loss outcomes,” Moin says.

She believes the online program is promising largely because of its potential to appeal to a number of different demographic groups.

“An intensive online lifestyle change program can reach many Veterans who cannot or will not participate in an in-person program,” Moin says. “Veterans who may benefit from online delivery include those living in rural areas where travel to a VA facility is more burdensome; employed Veterans who can’t participate in an in-person program during regular work hours; Veterans with major family support obligations or caregiving responsibilities; and women Veterans who may feel less comfortable in the typically male-dominated in-person groups.

“In essence,” she adds, “an online program like DPP may become a valuable option for many Veterans who are not already participating in MOVE!”

Dr. Tannaz Moin says prediabetes can usually be reversed through basic lifestyle changes: eating right, losing weight, and exercising more. (Photo by Scott Hathaway)

Word in the medical community is that prediabetes is a reversible condition. Dr. Tannaz Moin, an endocrinologist at the Los Angeles VA, also subscribes to that belief.

But reversing prediabetes doesn’t happen by snapping your fingers. One must commit to making key lifestyle changes so his or her blood sugar levels, or hemoglobin A1c, can return to a normal range, she says.

“The way I like to think about prediabetes is that it’s an opportunity to prevent diabetes,” she says. “That’s the really important condition to prevent. But the key point about prediabetes is not so much that it itself is such a dangerous condition, but it’s a precursor to something that we all know can have significant morbidity and mortality associated with it. That’s Type 2 diabetes. That’s the way I’ve always thought about it. We have an opportunity to be proactive and prevent Type 2 diabetes.”

Moin advocates basic lifestyle changes: eating right, losing weight, and exercising more. Learning how to eat a balanced diet with fewer calories—a figure that varies depending on a person’s weight—is critical to shedding pounds, she says. But she hesitates to suggest how many calories a person should cut out of a diet.

“Unlike other conditions, such as Type 2 diabetes, for which studies have shown the benefits of limiting carbohydrate intake, nutritional guidance for prediabetes is somewhat more vague,” Moin says. “We usually recommend a balanced diet that has a lower number of calories to help a person lose at least 5 percent, ideally 7 percent, of his or her body weight.”

In terms of exercise, Moin recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity a week. Brisk walking outdoors or on a treadmill, or an exercise where someone may feel a little out of breath, is appropriate, she says.

“In broad strokes, those are the basic principles,” she says. “The best way for someone to make those changes is a program like the Diabetes Prevention Program [DPP, see main story], which is structured, provides iterative skill building [sessions built on concepts over time], and has a certain degree of intensity. A 12-month program like DPP is what we would consider the gold standard, the best way for us to be able to ensure that someone can, in fact, make those changes. DPP has a very strong evidence-base for preventing Type 2 diabetes.”

“But people can participate in all types of weight-loss programs,” she adds. “There’s also Weight Watchers and VA’s program MOVE!. There are a lot of options when it comes to making healthy choices and losing weight. Some of these programs have been studied and shown to prevent Type 2 diabetes.”

More than 80 million U.S. adults have prediabetes, but it’s not known how many Veterans live with the condition. According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), up to 70 percent of people with prediabetes will eventually develop Type 2 diabetes. Most adults with diabetes have Type 2 diabetes, and nearly 25 percent of VA’s patient population lives with diabetes.

Measuring one’s hemoglobin A1c level is considered the standard way of determining if someone has diabetes. Hemoglobin, which carries oxygen through the body, is a protein found in red blood cells. When blood sugar, or glucose, is attached to hemoglobin, it’s referred to as A1c. An A1c level below 5.7 percent is considered normal, but a level between 5.7 percent and 6.4 percent signals prediabetes. When the A1c is more than 6.5 percent, one has Type 2 diabetes.

One of the first steps to addressing the problem, figuring out if someone even has prediabetes, is “tricky,” Moin says. People with prediabetes often show no symptoms, she notes. ADA recommends that diabetes testing start at age 45 for adults who are overweight.

“In concept, it just takes a blood test that a primary care provider can order to determine if someone has prediabetes,” says Laura Damschroder, an expert in wellness programs at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System who collaborates with Moin on her research. “But in a nutshell, not every provider does this, and not every patient is aware of the test results even if he or she has had the test.”

Moin says VA and the private medical community must do a better job of raising prediabetes awareness.

“Veterans tend to be more overweight and obese than the general population, and they tend to be a little older and sicker,” she says. “Whatever we can do to help them prevent diabetes is key. It’s also important that we help them improve their quality of life. Studies have shown that making lifestyle changes, losing weight, and being active help people feel better.”

--- Mike Richman

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates