Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

September 29, 2016

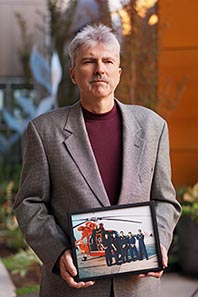

Veteran Ian Phillips was successfully treated with the new-generation hepatitis C drugs. Read his story below. (Photo by Christopher Pacheco)

A database study has found that new drug regimens for hepatitis C have resulted in "remarkably high" cure rates among patients in VA's national health care system.

The study appears in the September 2016 issue of the journal Gastroenterology.

Of the more than 17,000 Veterans in the study, all chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus at baseline, 75 percent to 93 percent had no detectable levels of the disease in their blood for 12 or more weeks after the end of treatment. The therapy regimens lasted 8 to 24 weeks, depending on patient characteristics.

The VA researchers analyzed data from four subgroups of patients infected with hepatitis C—genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4—and found that genotype 1 patients showed the highest cure rates and genotype 3 the lowest. Genotype 1 was by far the most common type of infection among the four subgroups.

"Modern direct-acting antiviral drugs for hepatitis C far outperform our older options in terms of efficacy and tolerability."

The study group of more than 17,000 Veterans included more than 11,000 patients with confirmed or likely cirrhosis, a liver disease that can result from hepatitis C, among other causes. The study team found "surprisingly high" response rates of around 87 percent in this group.

The overall results were consistent with those from earlier clinical trials that led to FDA approval of the three new drug regimens in the study: sofosbuvir (SOF), ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (LDV/SOF) and paritaprevir/ ritonavir/ ombitasvir and dasabuvir (PrOD).

The drugs, introduced in 2013 and 2014, have been credited with revolutionizing hepatitis C treatment, which means a cure is now in reach for the vast majority of patients infected with the virus. Previously, using earlier drug regimens, most patients could expect, at best, only a 50 percent chance of a cure.

"Our results demonstrate that LDV/SOF, PrOD and SOF regimens can achieve remarkably high SVR [sustained virologic response] rates in real-world clinical practice," the VA researchers wrote.

The new drug regimens examined in the study do not contain interferon, which has troublesome side effects such as fever, fatigue, and low blood counts. The newer drugs are considered far more tolerable than the older interferon-based antiviral regimens, although they are far more expensive.

The researchers extracted anonymous data on all patients in VA care who received HCV antiviral treatments between January 2014 and June 2015 using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, a national, continually updated repository of data from VA's computerized patient records.

The study's optimistic finding bodes well for Veterans and others infected with the hepatitis C virus, according to coauthors Dr. Lauren Beste and Dr. George Ioannou, specialists in internal medicine and hepatology, respectively, with the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle.

"Modern direct-acting antiviral drugs for hepatitis C far outperform our older options in terms of efficacy and tolerability," said the two researchers in an email interview. "With older drugs, most patients could not undergo antiviral treatment because they had contraindications or medication side effects. With newer options, almost anyone can safely undergo treatment for hepatitis C."

This comes as VA is dedicating significant funds to help greater numbers of patients with hepatitis C. For fiscal year 2016, VA anticipates spending about $1 billion on new hepatitis C drugs, compared with nearly $700 million in FY 2015. The increased funding has led to far more Veterans being treated than ever before for the condition.

Ioannou notes that "since February 2016, all VA facilities in the country have had unrestricted access to all antiviral meds for all patients. VA has allocated money for these drugs in the quantity needed and to my knowledge is the only health care system in the world to have done so."

VA has long led the country in screening for and treating hepatitis C. As of mid-September 2016, the agency had treated more than 100,000 Veterans infected with the virus. More than 68,000 of these patients had been treated with the new highly effective antivirals.

VA research continues to expand knowledge of the disease through scientific studies focused on effective care, screening, and health care delivery. Some studies look at particular groups of hepatitis C patients—for example, female Veterans, or those with complicated medical conditions in addition to hepatitis C.

Veterans can find more information on VA care for hepatitis C at www.hepatitis.va.gov.

Coast Guard Veteran Ian Phillips was cured of hepatitis C after a two-decade ordeal with the virus. (Photo by Christopher Pacheco)

For more than two decades, Ian Phillips lived with an active case of hepatitis C. He was mostly asymptomatic, although like many other Veterans the virus caused him to acquire cirrhosis, a deterioration of the liver.

Phillips, who spent 10 years in the Coast Guard, rarely volunteered to others that he was carrying hepatitis C. But all along he was fighting a personal battle, worrying that the virus was eating away at his liver, and that he was inching closer to needing a transplant.

It was like a "ticking time bomb," he says.

That bomb has been defused for now. The hepatitis C virus (HCV) has been undetectable in Phillips' blood for the past year, and his cirrhosis has stabilized, allowing him to regain some liver function. His doctors tell him his hepatitis is totally cured and will not come back unless he gets re-infected.

All of that is thanks to his three-month stint on the drug regimen ledipasvir/sofosbavir - a relatively new but very expensive combination that is becoming more available to Veterans with hepatitis C (see main story). The regimen also included ribavirin, which has been in use for some time. Phillips, who was treated in regular clinical care, says he experienced minimal side effects from the drugs.

He hopes never to relive what was a wrenching period in his life.

"It was difficult for many years while the virus was still active," he says. "Hep C is not something you want to go around and tell everybody about. It's a tough thing."

Phillips was treated at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle by Dr. Lauren Beste, a specialist in internal medicine.

"Dr. Beste is one of the most fantastic doctors I've ever encountered," he says. "And to consider that she saved my life and has been just wonderful all the way through, almost like a family member. Pretty incredible. She really cares."

Phillips, now 52, began serving in the Coast Guard in 1984 and was eventually stationed in Miami as an HH-65-A helicopter flight mechanic from 1993 to 1997, with responsibilities for fueling and maintenance. He earned his aircrew wings at the time.

In 1993, Phillips became part of operations Able Manner and Able Vigil, in which Coast Guard vessels rescued thousands of Haitian and Cuban migrants in the Caribbean and prevented them from illegally entering the United States. Phillips, with cuts on his hands from working in the engine room as a mechanic, helped a lot of the migrants off of their boats and onto his cutter. Wearing gloves that were much thinner and less durable than those required today, he came in contact with bodily fluids and human wastes.

Shortly after, while donating at a Red Cross blood drive in Miami, he was told he had hepatitis C.

"That's where it all started," he says. "It was really frightening."

Later in the 1990s, Phillips took part in two HCV trials at the University of Miami and one at the University of Washington. All of the studies involved the drug interferon, which can cause nasty side effects, combined with ribavirin. None of the treatments worked, compounded by the fact that Phillips experienced body aches and other flu-like side effects from the interferon.

The harsh daily reality continued for Phillips, a genotype 3 patient, one of the least common but most difficult-to-cure hepatitis C infections. But he ultimately became a candidate for HCV therapy with the newer drugs. He started on the ledipasvir/sofosbuvir and ribavirin regimen in February 2015 at the VA Puget Sound.

Today, Phillips resides in Port Orchard, Washington, near Seattle, and spends time helping his brother-in-law, a Vietnam Vet, get treatment for leukemia.

Phillips says he is living with what he calls a "new lease on life."

"I don't have the virus hanging over my head," he says. "I have the chance that I could have complications like liver cancer, because you have a high percentage of people getting that with cirrhosis. But knowing that the hep C is no longer attacking my liver...I feel healthy, I hike, I'm active. I'm no longer carrying around that stigma, the ticking time bomb of the virus. It's a wonderful thing."