Office of Research & Development |

|

VA Research Currents archive

July 23, 2015

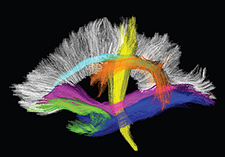

Diffusion MRI images such as these can reveal subtle white-matter damage in the brain. (Courtesy of L. McEvoy)

If you want to keep your brain healthy as you age—and who doesn't?—nip hypertension in the bud.

That's the message of a new report from the Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging, now appearing in the journal Hypertension, published by the American Heart Association.

VA and university researchers, based mainly in San Diego, imaged the brains of more than 300 Vietnam-era Veterans. They found similar white-matter damage in those with high blood pressure whether the condition was relatively new or long-standing. The effects were also similar regardless of whether the high blood pressure was controlled through medication.

"The results suggest that prevention—rather than management of hypertension—may be vital to preserving brain health in aging," wrote the researchers.

In other words, once blood pressure rises above normal, subtle but harmful brain changes can occur rather quickly—perhaps within a year or two. And those changes may be hard to reverse, even if blood pressure is nudged back into the normal range with treatment.

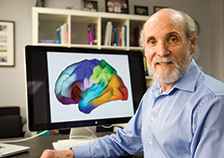

Dr. William Kremen is with the Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and the Center for Behavioral Genomics at UCSD. (Photo by Kevin Walsh)

"The findings suggest that doctors should be aggressive in preventing hypertension—for example, educating patients who are only pre-hypertensive about the importance of lifestyle changes," says senior author Dr. William Kremen. "Patients may be more willing to make those changes if they realize that their brains may be affected by hypertension, even if medications can be used to adequately control blood pressure."

Kremen, a psychologist, is with the Center of Excellence for Stress and Mental Health at the VA San Diego Healthcare System and the Center for Behavioral Genomics at the University of California, San Diego.

Lead author Dr. Linda McEvoy adds that most people associate high blood pressure only with strokes, but the potential effects on the brain are much wider—including the insidious microscopic damage to white matter seen in her team's study. White matter acts like a highway in the brain, allowing for the relay of electrical signals between brain cells.

"People may be aware that high blood pressure increases the risk of stroke, which can lead to cognitive impairment and dementia, but many may not be aware that even in the absence of stroke, high blood pressure may be causing subtle cognitive decline," says McEvoy, an associate adjunct professor in the department of radiology at UCSD. "It can be contributing to some of the changes in our ability to think that we attribute to growing older. And hypertension-related brain damage can also make the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease worse, or make them appear earlier in the course of the disease than they would otherwise."

To date, most studies linking high blood pressure to poor brain health have focused on older people. Researchers are only now coming to understand how the condition can affect brain health in those who are middle-aged or even younger—and how fast those changes set in.

The 316 men in the study had an initial assessment and returned to the clinic nearly six years later for brain imaging and further exams. Some of the men had normal blood pressure on both occasions. Others had high blood pressure at both visits and were classified as longer-duration cases. Others had developed hypertension only in the interim—between visits—and were thus classified as shorter-duration cases.

Given the time frame of the study, the difference in duration between the short- and long-standing diagnoses was not great—only around five years or less. The researchers say more years of follow-up might in fact reveal increasing damage with longer-standing hypertension.

In any case, they say the results "suggest that hypertension has widespread effects on brain white matter" that begin early in the course of the disease and "may not be easily reversible."

The researchers used diffusion MRI, which tracks water molecules as they move through brain tissue. The method detects subtle microscopic damage to the brain's white matter. One example is decreasing diameter of the nerve fibers, or axons—the threadlike projections that relay messages from one brain cell to another. Another is a loss of myelin, the insulation around nerve fibers that enables them to function.

Emerging research suggests such subtle damage, measured at the micrometer scale, is not benign; it can translate into clinical symptoms.

For example, a 2013 study that involved Boston VA researchers linked "white matter microstructure" changes to poorer executive function and processing speed.

The results from the new research also complement those from a 2012 study by a team at the University of California, Davis, which found that even adults in early middle age could show white-matter damage related to high blood pressure. The study involved third-generation Framingham Heart Study participants, who were only about 40 years old, on average, and healthy overall. The study, published in 2012 in The Lancet Neurology, concluded that "subtle vascular brain injury develops insidiously during life, with discernible effects even in young adults. These findings emphasize the need for early and optimum control of blood pressure."

The Vietnam-era Veterans in the San Diego study were about 62 years old, on average, when they were scanned. So the findings may not be as stunning as those from the younger Framingham adults. Still, they underscore the importance of preventing high blood pressure in the first place, rather than trying to control it and stem its harmful effects on the brain and the rest of the body.

The latest report focuses only on microscopic white-matter damage. The San Diego team has also documented macroscopicwhite-matter damage, visible to the eye, that is also attributable to high blood pressure. Those results, based on the same Veterans, will be published in the future.

Researchers don't yet fully understand how hypertension damages the brain's white matter. But they do know that the condition affects the flow of blood—and thus oxygen—into these tissues.

"Other studies have shown that hypertension causes a number of changes to blood vessels, including the blood vessels supplying white matter," explains McEvoy. "These changes result in periods of hypoperfusion, or reduced blood flow, which results in reduced oxygen supply to the local tissue. Myelinated axons in the white matter appear to be highly susceptible to this disruption in oxygen supply."

The 316 men taking part in the Vietnam Era Twin Study of Aging are part of a larger group of volunteers who make up the Vietnam Twin Registry. The total registry contains data on some 7,000 middle-aged male twin pairs, all of whom served in the U.S. military during the Vietnam War. All the men served between 1964 and 1975.

Managed by VA's Seattle-based Epidemiologic Research and Information Center, the registry is among the largest twin registries in the nation, with members in all 50 states. It was initially formed to help answer questions about the long-term health effects of service in Vietnam, but today it serves as a resource for studies on a wide range of mental and physical health conditions.

McEvoy and Kremen's team received support from the National Institutes of Health and VA. Besides VA, participating institutions were the UCSD, Boston University, and the University of Southern California.