Office of Research & Development |

|

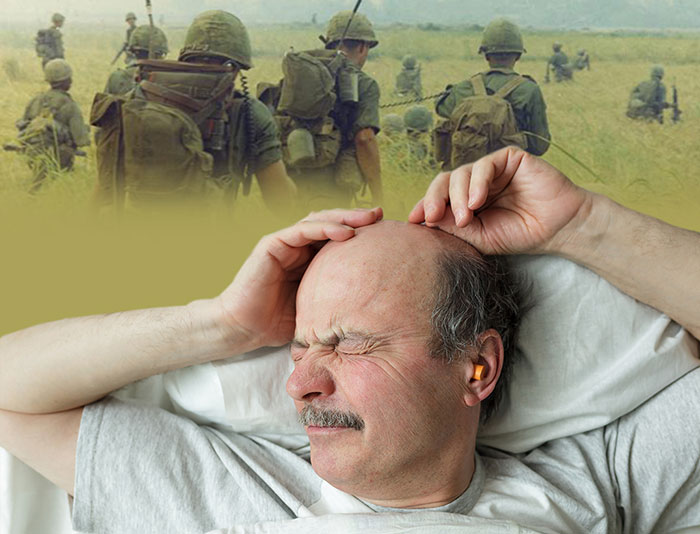

Many Veterans with combat-related PTSD experience nightmares. (Photos: ©iStock/Koldunov; National Archives)

February 8, 2018

By Mitch Mirkin

VA Research Communications

Dr. Murray Raskind is a psychiatrist and researcher at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System and the University of Washington. (Photo by Emerson Sanders)

A drug called prazosin, used widely in VA to help ease nightmares from posttraumatic stress disorder, did no better than placebo pills in a large multisite clinical trial sponsored by VA’s Cooperative Studies Program (CSP). The trial involved more than 300 combat Veterans.

The results appear in the Feb. 8 New England Journal of Medicine.

Despite the drug’s failure to outperform placebo in the trial, the researchers contend there may be subgroups of Veterans who do in fact benefit from the treatment.

“What the trial taught us is that not every Veteran who subjectively reports nightmares in the context of a PTSD diagnosis is going to respond to prazosin. There’s clearly a subtype of persons that does respond,” says Dr. Murray Raskind, who led the study.

"Based on the prior studies where the drug clearly worked, I hope VA doesn't discourage the use of prazosin."

Raskind is a psychiatrist at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System and the University of Washington. He pioneered the use of prazosin among combat Veterans starting in the late 1990s. Before then, the inexpensive generic drug had been used for decades to treat high blood pressure. It blocks norepinephrine, a hormone related to adrenaline, and crosses the blood-brain barrier. It also treats benign enlargement of the prostate, a common condition in older men.

On the basis of positive findings from several smaller trials, the drug was eventually included in the PTSD clinical practice guideline issued by VA and the Department of Defense.

The latest version of the guideline, from June 2017, backs off from recommending the drug, based on results from the CSP trial that were made available to the guideline committee prior to the study’s publication.

Million Veteran Program director speaks at international forum

2023 VA Women's Health Research Conference

Self-harm is underrecognized in Gulf War Veterans

Head trauma, PTSD may increase genetic variant's impact on Alzheimer's risk

The committee had this to say in the guideline:

“We recognize that these recommendations constitute a significant reversal of prazosin’s role in the current management of PTSD. We are recommending neither for nor against the continuation of prazosin in patients who believe it to be beneficial; the decision to stop or continue prazosin should be individualized and made using [shared decision-making]. If patients and/or providers decide to discontinue prazosin, we suggest a slow taper of the dose, while monitoring for symptom worsening or reappearance. Prazosin may need to be continued or restarted in some patients.”

Raskind and other advocates of prazosin firmly believe clinicians who have had success with the drug should continue to prescribe it.

Dr. Murray Stein, also an author on the study, and a psychiatrist and researcher with VA and the University of California, San Diego, says the results of the CSP trial were “surprising and disappointing.”

“Based on the prior studies where the drug clearly worked, I hope VA doesn’t discourage the use of prazosin. I believe that its availability and use within VA has been a boon to many patients with PTSD.”

The CSP trial included 304 combat Veterans at 13 VA medical centers. Half received prazosin, and half placebo. After 26 weeks, there were slight improvements in measures of nightmares and sleep distress, as well as in other PTSD symptoms, but there was no statistical difference between the two groups.

Raskind says that out of an abundance of caution, the study recruited only patients who were fairly stable, and not at risk of suicide or other self-harm or violent behavior.

One of the study’s exclusion criteria read as follows:

“Severe psychiatric instability or severe situational life crises, including evidence of being actively suicidal or homicidal, or any behavior which poses an immediate danger to patient or others.”

In retrospect, Raskind says that may have excluded the very patients who would potentially benefit from the drug.

That group of patients, says the longtime VA clinician-researcher, tends to have higher than normal activity in the body’s adrenergic system. Think adrenaline.

“The folks with the hyper-adrenergic subtype are the ones who are clinically unstable,” explains Raskind. “They are so distressed by their hyperarousal symptoms during the day, and their awakenings at night, that they’re usually drinking quite heavily to try to suppress the symptoms. And they’re very often involved in disputes within their family, or with the law.”

The clinical profile is also marked by higher blood pressure.

“When I look back at my practice, and the people I’ve treated successfully with prazosin over the years, most had higher blood pressure than expected for their demographic group, and they all had distressed awakenings at night, with sweating and thrashing around in the bed, and a rapid heartbeat when they woke up,” says Raskind.

He notes that in contrast, the CSP trial “didn’t have many folks with higher blood pressure.” And they scored as “light” alcohol consumers, versus the heavy drinking patterns Raskind has seen in most of his successful prazosin cases.

The psychiatrist elaborates further on what he sees as the classic profile of the prazosin responder:

“During dreams, there’s thrashing around. They almost rip up the bedsheets. It’s accompanied by sweating—they wake up and the bed is drenched. They notice their heart’s beating hard. Their bed partners, if they haven’t moved to another room—and many do—note that during dreams, the motor tone is preserved in the large muscles. When most people dream, their large muscles are essentially paralyzed. During REM sleep, our eye muscles move back and forth, but the rest of our muscles are essentially paralyzed. But during dreams, these prazosin responders have a lot of large muscle activity, which could potentially be dangerous to their bed partners.”

Raskind’s practice has focused on Veterans who saw heavy combat in Vietnam, and on more recent Veterans, often from special forces units, with “multiple, horrific deployments.”

Those who respond well to prazosin, he says, might experience “extreme hyperarousal, fear-associated episodes when they go into a supermarket—into the meat section, say, where they smell the meat and it reminds them of their buddy who was blown to smithereens by a mortar. Or they go to the Asian part of town and smell fish sauce. Or hear helicopter rotors overhead. It’s an intense adrenaline response. That’s how they describe it—an adrenaline storm.”

The CSP trial also excluded any combat Veteran who was already on prazosin, or had tried it in the past. Stein says that may be another reason why the study population ended up being skewed toward prazosin non-responders.

“There’s widespread availability of prazosin within VA—which is a good thing—leading to many patients already having benefited from the drug and not entering the clinical trial.”

By the same token, “those who entered may have been more refractory [resistant] to a variety of treatments, including prazosin.” He admits it’s difficult to prove this theory.

Both he and Raskind see the CSP trial as a learning experience, perhaps moving VA clinicians a step closer to “personalized” or “precision” medicine for those with PTSD.

“In general,” says Stein, “we have ‘failed’ trials in psychiatry for many compounds, including prazosin, because we don’t know who they work for and who they don’t. The hypothesis that patients with high adrenergic activity will respond to prazosin is interesting and sensible, but still preliminary. But yes, even being able to test that hypothesis going forward in a new study is a big step forward for ‘precision psychiatry.’”

Raskind agrees. “I think the study was instructive. We’ve got to look for the subtype who will respond. Whether with psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, we have to figure out which of our Veterans have the characteristics that predict success and tolerability of the treatments we’re prescribing.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates