Office of Research & Development |

|

Dr. Matthew Tuck is an internist at the Washington DC VA Medical Center and lead site investigator for the African American Cardiovascular Pharmacogenomics Consortium (ACCOuNT). (Photo by Mike Richman)

May 22, 2019

By Mike Richman

VA Research Communications

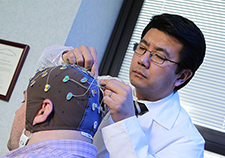

Dr. Matthew Tuck checks in with patient Willie White, a Vietnam-era Air Force Veteran who is enrolled in the ACCOuNT study. (Photo by Mike Richman)

Imagine a scenario in which a patient is at risk for blood clots. His doctor checks the patient’s genetic makeup and decides on a particular blood thinner, one of several available. The drug works as expected, improving blood flow and reducing the chances of heart attack, stroke, or death.

Such an approach to prescribing drugs is becoming more and more commonplace. In fact, it’s part of a revolution in medicine called pharmacogenomics, the study of how genes influence the way a person responds to drugs.

But are all patients benefiting?

Dr. Matthew Tuck, an internist at the Washington DC VA Medical Center, is concerned that African Americans have been largely excluded from this revolution, especially when it comes to drugs for heart diseases. He’s a member of the African American Cardiovascular Pharmacogenomics Consortium (ACCOuNT). It was created in 2016 to advance the field of pharmacogenomics, with an emphasis on the cardiovascular health of African Americans.

“Most studies on pharmacogenomics have been conducted nearly exclusively on Americans of European descent, leading to health disparities,” says Tuck, who is also an associate professor at The George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Maryland. “Also, studies have largely overlooked differences in adverse reactions to drugs, according to ethnicity.”

"In an ideal situation, a health care provider would know whether a certain drug would be appropriate for a person before it’s prescribed."

Pharmacogenomics is a branch of precision medicine, an emerging approach in health care that takes into account a person’s gene variants and his or her environment and lifestyle. The goal of pharmacogenomics is “making sure the right person receives the right drug at the right dose,” as Tuck put it.

“In an ideal situation, a health care provider would know whether a certain drug would be appropriate for a person before it’s prescribed,” he says. “Precision medicine, as the name implies, uses a patient’s genetics to more precisely and accurately inform prescribing practices.”

Currently, more than 500 African Americans are enrolled in the ACCOuNT study. About 30 percent are from the Washington VA, making it the largest recruiting site to date. The other participating sites are The George Washington University, Northwestern University in Chicago, the University of Chicago, the University of Illinois at Chicago, Stanford University in California, and Shenandoah University in Virginia. Tuck is the only ACCOuNT researcher with VA affiliation.

The ultimate goal is to enroll at least 1,500 African Americans. They are sharing their genetic information through blood samples for what Tuck says will be the largest bank of pharmacogenomic data that is focused solely on African Americans.

“We envision that when African Americans enter the health care system, in other words when they see their primary care provider, they’ll submit a blood sample for genotyping,” Tuck says. “From then on, anytime a health care professional wants to prescribe a new drug, he or she will be better informed about what medications work better, less well, or are unsafe for the patient. Everyone, not only African Americans, will hopefully benefit from the genomics revolution when it comes to drugs.”

Many studies have identified gene variants specific to African Americans that place them at greater risk for high blood pressure, which can lead to heart disease. Plus, research has noted racial differences in the rates and severity of drug reactions. One study showed that African Americans with a drug-induced liver injury are at greater risk for health complications, with higher rates of hospitalization and death, compared to white people with the same injury.

Adverse drug reactions are the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States. They account for 100,000 deaths per year and markedly increased health care costs.

In VA, Tuck says, the need to link the right drug to the person’s genotype is only going to become more of an issue over time because the agency’s minority population is rising rapidly. VA projects that in less than 20 years, about 32% of its patients will be minorities, and more than 16% of the Veterans it treats will be African Americans, who make up 14% of the U.S. population.

Landmark MVP study hits quarter-million enrollment mark

International study involving VA yields new insight on schizophrenia genes

In pursuit of precision medicine for PTSD

Genomic medicine: The next frontiers in VA

Large genomic cohorts can help with the discovery of genetic markers that predict response to medications. VA’s Million Veteran Program (MVP), for example, currently has more than 750,000 Veterans enrolled, making it the largest genomic database tied to a health care system. The racial and ethnic makeup of the enrollees is diverse, with African Americans at 18% and Hispanics at 6.5%, according to MVP Director Dr. Sumitra Muralidhar.

Because of the large number of African Americans in the cohort, she says, some of the ongoing studies using MVP data have analyzed the role of genetics in that population. But, she adds, doctors can’t use MVP data directly for individual clinical care since the program is a research cohort. The results must be validated in a manner that complies with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988, which sets guidelines for laboratory testing to ensure the accuracy, reliability, and timeliness of patient results.

An MVP pharmacogenomic analysis is in the early stages of planning, Muralidhar notes.

The information collected by ACCOuNT is being incorporated into a database that will be publicly searchable. The researchers are also including genomic data on African Americans from the Gene Expression Omnibus, an international public repository that archives and distributes genomic data sets. Plus, social and demographic factors that help to explain drug responses that may not be linked to genetics will be in the database.

“These details will guide all of the major stakeholders—doctors, pharmacists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and patients—in choosing the right drug for treating African Americans,” Tuck says. “The scientific community will be able to build off of our work, with the intent that there will be a greater discovery of African American-specific biomarkers.”

He hopes the information will also enhance VA’s electronic health records system, which is the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS), to better meet the needs of African Americans and other minorities when it comes to prescribing drugs. (VA is currently transitioning from CPRS and adopting the Department of Defense’s electronic medical records system to allow for seamless care between the agencies.)

“Electronic health records like CPRS are a rich resource of information,” Tuck says. “Currently, physicians and other health care providers are able to note adverse drug reactions as an allergy within CPRS after they have already occurred. We’d like to see the electronic health record deliver pharmacogenomic information to health professionals at the point of a patient encounter, so providers can determine if a patient’s genetics impact the drug they are considering prescribing.”

ACCOuNT is aiming to pinpoint how African Americans respond to drugs with cardiovascular applications, with research focusing on four blood-thinning medications that can prevent heart attack, stroke, or other heart problems: clopidogrel (commercial name Plavix), warfarin (Coumadin), apixaban (Eliquis), and rivaroxaban (Xarelto). The information that is gleaned about these drugs will be especially important at the Washington DC VA Medical Center, where the majority of patients are African Americans, according to Tuck.

Tuck also points out that clopidogrel, for example, has been found to be less effective in patients with certain variants of genes that affect the way the drug is broken down.

“Compared with white people, people of Asian or Pacific island ancestry have had increased rates of cardiovascular incidents, such as heart attack and stroke, when prescribed clopidogrel at its usual dose,” he says. “Unfortunately, as with other cardiovascular drugs, studies on the pharmacogenomics of clopidogrel have largely not included African Americans, leaving us wondering about the effectiveness of clopidogrel in this population.”

The four drugs being studied are designed to prevent venous thromboembolism, in which a blood clot forms most often in the deep veins of the leg, groin or arm, and eventually lodges in the lungs. Tuck notes that because African Americans suffer high rates of this condition, he and his team plan to collect data on bleeding and embolism. He hopes this information, along with the genetic data, will predict which patients will and won’t do well on certain drugs.

Tuck serves as the ACCOuNT site investigator at the Washington VA. The study is funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The grant is largely the result of the emphasis placed by the Obama administration on improving precision medicine for African Americans.

In 2015, President Obama launched the Precision Medicine Initiative, a new research effort to revolutionize how health is improved and diseases are treated. It avoids the “one size fits all approach” and takes into account peoples’ genes, environments, and lifestyles in the context of health care.

The National Institutes of Health runs the program. It launched a study that aims to involve at least 1 million people who are providing genetic data, biological samples, and other information about their health. VA and the Department of Defense are also involved in the Precision Medicine Initiative.

In the private sector, clinicians at some medical centers have been using pharmacogenomic biomarkers in drug labeling put forth by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. But “medical literature would suggest that clinicians are doing a poor job of it,” Tuck says, noting that universal implementation of pharmacogenomics screening is facing challenges. Some health care centers are also adopting recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium, an international body that is interested in facilitating use of pharmacogenomic tests for patient care, on how genetic test results can be used to optimize drug therapy.

Inova, a nonprofit health care network of hospitals and doctors in the Washington, D.C., area, has launched a program to screen newborns for genetic information, with the consent of their parents. The goal, Tuck says, is for Inova to have the information as the children grow up in order to customize drug prescriptions.

“Inova is using it to really advertise its health care system as one that’s very innovative,” he says. “Most hospitals are not at that point yet.”

ACCOuNT has created an interactive system that is embedded into the medical record at the University of Chicago. The system provides genetic information to health care providers at the university to help them decide which drugs are the safest to prescribe for patients who have been genotyped.

Tuck says he’d like to see such a system integrated into VA’s electronic health network. The system would need to be tested on a trial basis, he notes.

In the future, Tuck and his ACCOuNT colleagues hope to pursue other pharmacogenomic studies on African Americans.

“One area we’ve entertained that deserves exploration is the pharmacogenomics of African Americans who acquire cancers while on cardiovascular drugs, such as breast, colon, lung, and skin cancer,” he says. “We know that cancers have their own unique genetics, in turn leading to differences in drug response. We hope to receive funding to better understand this interplay.”

VA Research Currents archives || Sign up for VA Research updates